Accessibility

Anything that’s designed is used to complete an activity.

- A coffee maker is used to make coffee.

- A poster about the flu is used to learn information about the importance of vaccines.

- An amusement park is used to have fun.

- A credit card (and the systems it works within) are used to purchase a smartphone.

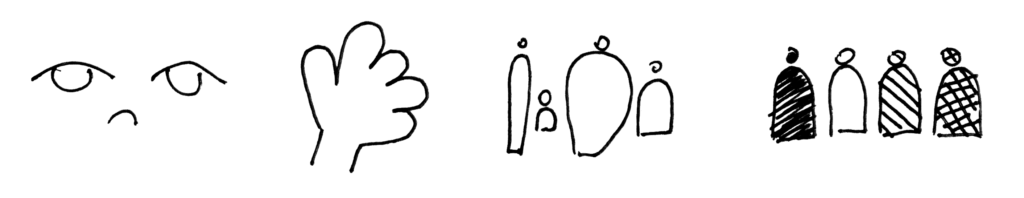

When people use design to complete activities, their experience is impacted by a few things.

- The context where they use the design: the weather, social norms, laws, noises, and other aspects of the person’s surroundings

- The person’s makeup: their physical characteristics, emotional state, relationships, personality, and aspects that form their identity

- The design: its style, size, material, and makeup

When contextual factors inhibit use, access for all or certain people is limited or maybe even denied. When a design is created only for a certain group of people, others are denied access. Two of our most impactful tasks as designers are:

- Identify where and when access is being limited

- Implement changes/new design/whatever to improve accessibility

Too often, designers are to blame for limiting access because the things we create are short-sighted. But sometimes, politics, social norms, prevailing attitudes, and long-reinforced systems keep people from getting what they need.

What About Usability?

Some of the examples I give below could be usability issues and not about access. Usability and accessibility are different.

- Usability is a measure of to what degree a design can be used. Design that can be used, but not very well, can still be accessed, though the user experience is not a very good one.

- Accessibility is a measure of a person’s ability to use or not to use a design. A product, service, or system is either accessible, or it’s not.

For example, an app for buying homes can be hard to navigate with confusing menus and terribly written listings, but it can still be used. It would not be very usable, but someone would still be able to access it. If the app required users to input a credit card number in order to see home listings, it would block access for anyone who does not have a credit card or would be uncomfortable sharing this information. The first example reduces usability, the second blocks all access.

Ways People are Denied Access

Sometimes, a design is made in such a way that people can’t use it to do what they want to do. The design—whether it be a ladder, voting machine, bus, or smartphone—blocks the person. The design (and the designers who made it) are to blame for withholding access.

This is not okay. The designer’s job is to create outcomes that facilitate access—that empower people to make coffee or have fun or worship or take care of their family or whatever. Products, services, and systems should be inclusive (and it is actually more profitable for our clients when it includes diverse communities) (Jean-Baptiste, 2020).

Let’s take a look at how design can block access so we’ll better know how to identify it when these barriers are present.

Design Does Not Match the Person’s Characteristics

This example is pretty straightforward. When a design’s features and format do not match a person’s physical makeup, they cannot use the design.

- A library building can only be entered using stairs. Anyone who uses a wheelchair cannot access the building.

- Text on a menu is very small. Anyone who cannot see well, cannot read the menu.

Design Does Not Match the Ways a Person Acts

People act and behave differently. Some products, services, and systems are designed in ways that block people who act or express themselves differently.

- A gated neighborhood homeowner’s association blocks people with noise violations from moving in.

- Signage in Chinese cannot be read by someone who only speaks German.

Design Requires a Person to Have Certain Knowledge or Skills

People have different knowledge sets and experiences. Products, services, and systems that require a person to have certain knowledge, skills, experience, or standing block others who do not have these knowledge sets.

- A printing press can only be successfully used by people who know how to use one.

- A student who has not learned design research methods will not be able to develop and operate a research project.

Design Does Not Account for a Person’s Values and Identity

A person’s values represent what they hold as desirable and ideal. If a product’s visual style or meaning opposes a person’s values, the design will be misunderstood or avoided.

- A menu that features meat as the main course will be eschewed by a person who eats a vegetarian diet.

- A corporation that dictates policies to its employees will alienate workers who value shared governance and collaboration.

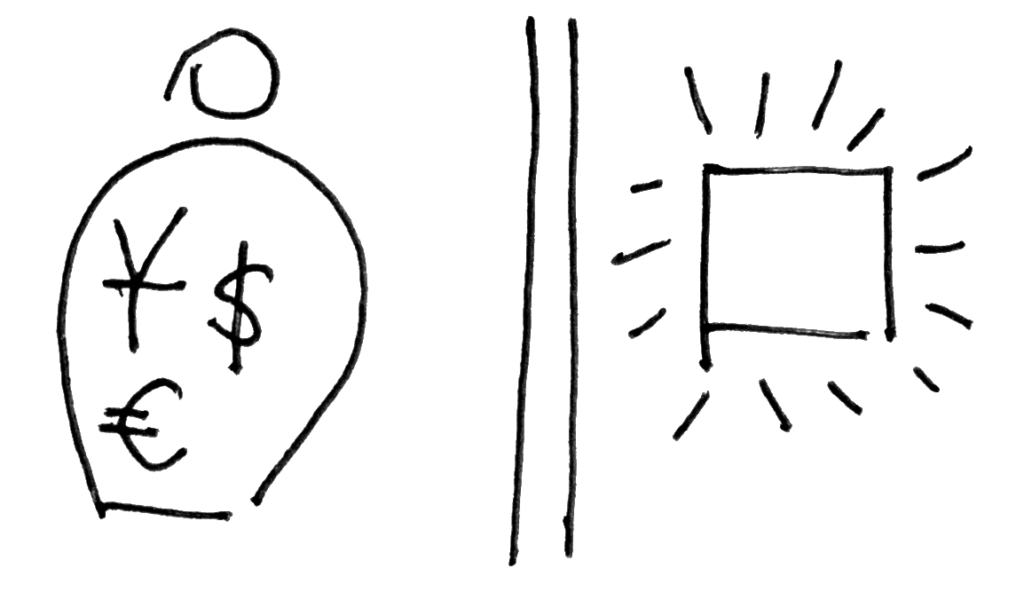

Design Does Not Account for a Person’s Social Class

People’s economic standing—how much money they have—represents their ability to make purchases or to give money or possessions away. When a product, service, or system costs more than a person can afford, it is out of reach and inaccessible.

- A poll tax blocks people from voting in elections.

- The high cost of a car forces people to ride buses in sprawling metropolitan areas.

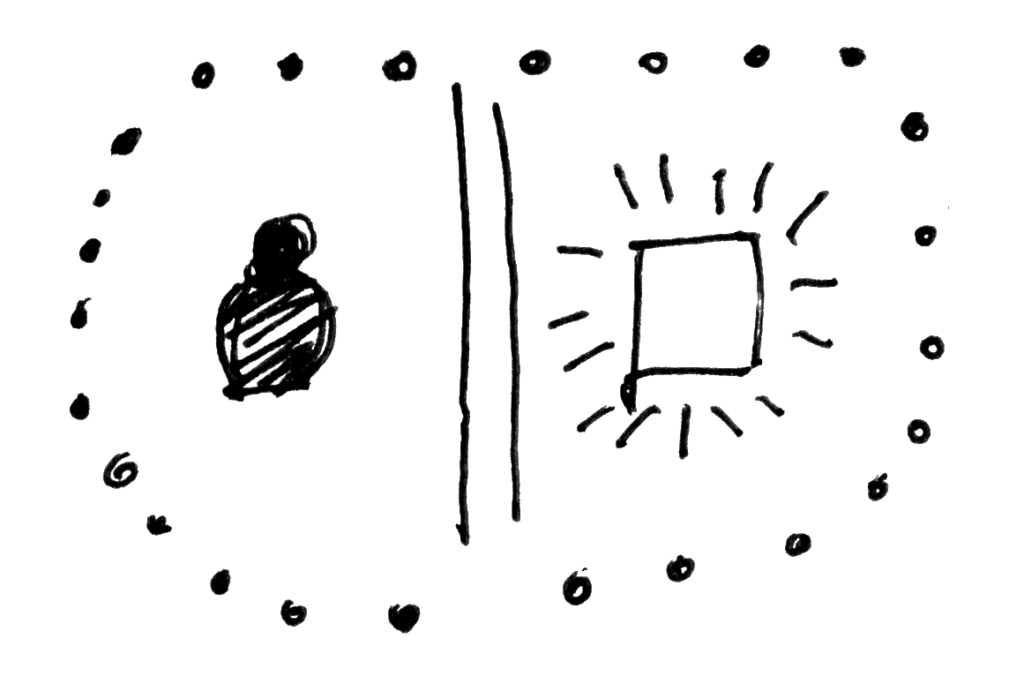

Contextual Factors Block Access

Laws, social norms, and attitudes in societies dictate what are and what are not acceptable behaviors. This can block access for people who travel to or live in these communities.

- Possession of marijuana over a certain amount is a felony, making it difficult for the offender to get a job for many years.

- Social norms and laws in some areas can prescribe what women can and cannot do.

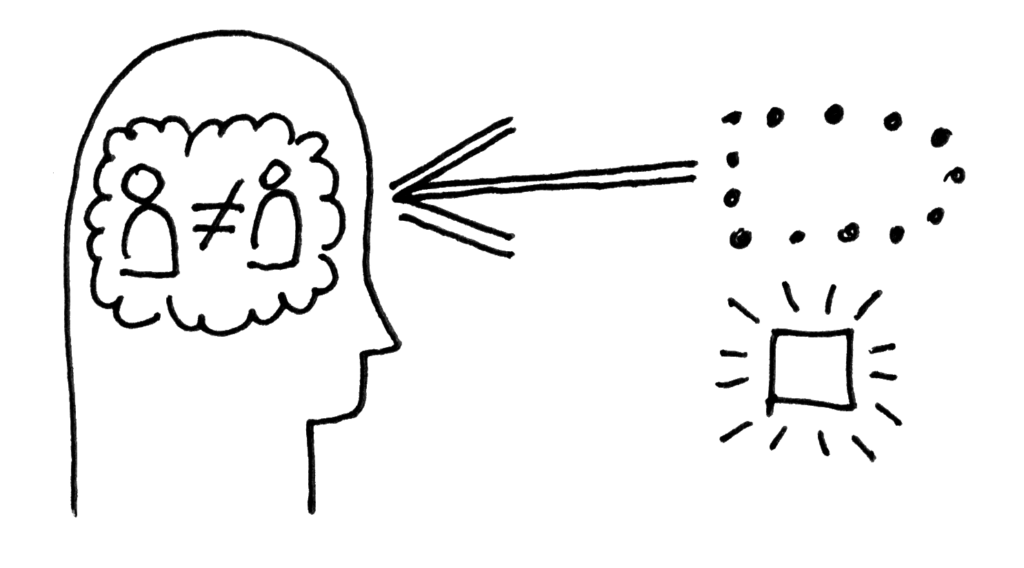

Context or Design Grooms People to Hold Damaging Values

Some cultures, communities, products, services, and systems can reinforce ideas and values to influence community members’ values. In response, some people can come to believe that one person or people group is “better” than another. They may even believe that they are not equal to others (Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, n.d.). The attitudes that emerge from this way of thinking perpetuate systems that reserve access for some people and remove it for others.

- YouTube commercials show images that depict homogenous communities of people fuel attitudes that only select groups are preferred or welcomed.

- Women and men develop a damaging view of their body type because they do not look like the models in print ads. As a result, they feel isolated and unable to be comfortable in public.

People come in all shapes and sizes and wear many hats (literally and figuratively.) Designed outcomes that do not represent people of all races, depict only one body type, neglect those who have a disability, or embrace all cultures and sexual orientations fuel structures that block people from being active members of society. Co-creating outcomes with people in the communities are the first step to revising structures that prevent access.

Where Can We Start Designing for Accessibility?

Let’s revisit those two key tasks designers must carry out to design for access:

- Identify where and when access is being limited.

- Implement changes/new design to restore access.

Our first step is to isolate how a design outcome or a context is blocking access. What about the design is “broken”? Is its style off-putting or unable to be understood by the person who will use it? Are the design’s features formatted in such a way that they block successful use? Is the design in a state of disrepair or is it configured where it blocks access? For example:

- A neighborhood community center’s doors automatically lock at 7 p.m., but meetings are scheduled till 10 p.m., so visitors get locked out if they leave to add coins to their parking meters.

- Wi-fi coverage does not reach an entire middle school building, so student-athletes cannot study using their Chromebooks before after-school practice.

- Information about diabetes treatment is written at a 10th-grade literacy level, but many in this neighborhood read at a 5th-grade level, so they can not read the instructions.

Once we have identified what is blocking access for people, we can co-create updated design outcomes or dismantle existing ones to restore access.

References

Jean-Baptiste, A. (2020). Building For Everyone. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.